What Really Happened With Ted Kennedy At Chappaquiddick

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

With the 2018 release of the film Chappaquiddick, decades-old questions have resurfaced about what really happened during the incident that not only claimed the life of young political staffer Mary Jo Kopechne but also sapped the presidential aspirations of Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy. Early reviews suggest the film fails to present any new information and does not adequately address the considerable damage control efforts taken by Kennedy's enormously powerful and influential family.

However, the conversation about the tragedy that forever reshaped an American political dynasty is now being revisited. What exactly happened the night of July 18 and early morning of July 19, 1969 on that quiet island adjacent Martha's Vineyard? Why did Kennedy wait so long — approximately 10 hours — before contacting authorities about the incident, and why have so many differing accounts of that fateful night materialized in the ensuing years?

Many of the answers to these questions are still shrouded in controversy, despite the cooperation of Kennedy and others involved in the incident with investigations that took place afterward. From their accounts, as well as a plethora of other publicly available information, here now is what we know about what really happened during the incident at Chappaquiddick.

The party on Chappaquiddick Island

In 1970, Massachusetts District Attorney Edmund Dinis ordered an inquest into the incident at Chappaquiddick. We'll get into the circumstances and findings of that investigation in a moment, but for now, we're citing it here, because it provided the most detailed, sworn-under-oath account by Sen. Ted Kennedy of what happened leading up to the fatal car crash.

According to Kennedy's testimony, published by The Smoking Gun, he was on Martha's Vineyard the day of the accident to participate in a sailing regatta. Later that evening, Kennedy said he went to the small sister island of Chappaquiddick for a get together arranged by his cousin, Joe Gargan, which was later revealed to be a reunion party of sorts for the "boiler room girls," a group of political staffers so named for their access to sensitive information on Robert F. Kennedy's presidential campaign. Mary Jo Kopechne, a known Bobby Kennedy acolyte, was one of them.

Kennedy testified that he was about to exit the gathering at around 11:15 p.m. when Kopechne told him she was also "desirous of leaving," so he offered her a ride back to her hotel in Edgartown, which was accessible only by ferry, across a 500 foot channel. Kennedy offered no information on how much, if any alcohol Kopechne consumed that day, and he claimed that earlier in the day, he had "about a third of a beer," and while at the gathering from approximately 8:30 p.m. to 9:00 p.m., he had two rum and cokes made with approximately two ounces of liquor. "Absolutely sober" was how he described his state of mind at the time of the accident. The senator also stressed that at no time had he ever had "any personal relationship whatsoever with Mary Jo Kopechne."

The fatal wrong turn

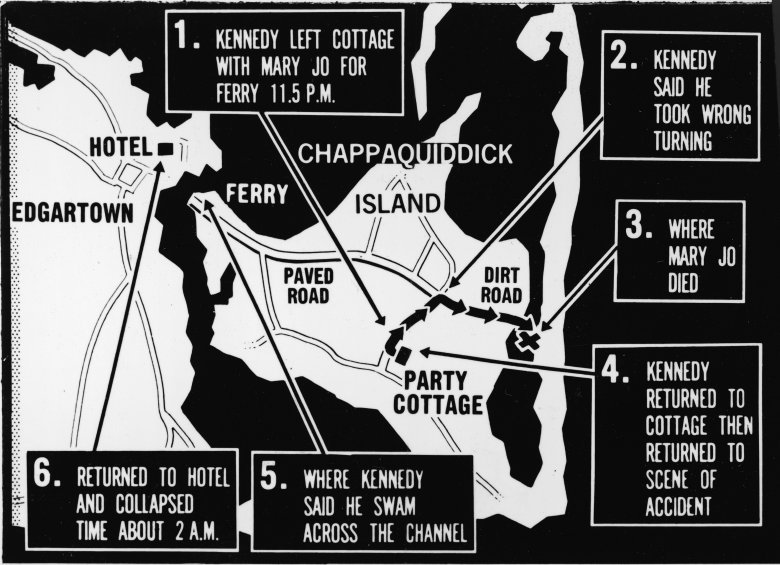

According to Kennedy's inquest testimony, his account of the accident is that he missed the turn to the ferry and instead headed down an unlit, unpaved road at 20 mph. Shortly after the missed turn, he drove the car off the Dyke Bridge, at which point the vehicle plunged into six or seven feet of water and quickly began to submerge. He managed to get out (although he couldn't recall how,) but Kopechne did not.

After being "swept away" by what he called "a tide that was flowing at an extraordinary rate," Kennedy said he returned to the vehicle and attempted seven or eight dives to try to retrieve Kopechne over a period of "15 – 20 minutes," but he was "hopelessly exhausted" and eventually gave up. After failing to save the young political operative, he allowed himself to be washed downshore, where he got himself safely to a bank and spent another 15 – 20 minutes "coughing up water" and trying to regain his strength.

At no point did Kennedy attempt to scream for help or to find a nearby house to call authorities. Instead, he collected himself and headed back to the cottage.

The failed rescue attempt

Ted Kennedy testified that it took another 15 minutes to make his way back to the cottage, and that along the way, he saw no lights from any other dwelling. Once there, he remained outside and got into the back of "a white vehicle" that was parked there. He then told partygoer and longtime friend, Ray LaRosa, to send out his cousin, Joe Gargan, and another longtime friend, Paul Markham. Kennedy said that he told LaRosa nothing about what had just happened, and that he didn't give Gargan and Markham specifics either, only that "there has been a terrible accident."

Gargan, Markham, and Kennedy then returned to the accident scene and spent approximately 45 minutes trying to retrieve Kopechne before they also gave up. Kennedy, due to his exhaustion, did not physically help, but said that he "made some suggestions."

Asked why the trio did not call the authorities at this point, Kennedy launched into a long explanation about how he, Gargan, and Markham all agreed that the incident needed to be reported, and he intended to do so by swimming across the channel (because the Ferry had stopped running) back to Edgartown, where there was a local police station. However, Kennedy said he was overcome by the physical strain of the swim, as well as his nightmarish thoughts of what had just transpired. When he reached his hotel room at the Shiretown Inn, he said he collapsed from exhaustion again, awoke around 2:30 a.m, then went back to bed. He did not report the accident to the police unit 10:00 a.m the next morning.

Also, before going to police, Kennedy, Gargan, and Markham returned to Chappaquiddick by ferry, so that Kennedy could use a private phone to attempt to call the family's personal attorney, Burke Marshall.

Kennedy's curious initial statement

According to excerpts from Leo Damore's book, Chappaquiddick: Power, Privilege, and the Ted Kennedy Cover-Up (via E! News), Kennedy's inquest testimony was problematic for a variety of reasons. For starters, it was full of information he omitted from the initial statement he gave to the police when he finally got around to reporting the incident. Two glaring omissions were: Kopechne's last name (Kennedy referred to her as "Miss Mary") and any mention at all of the alleged rescue attempt by Gargan and Markham.

Regardless of the stark lack of detail in Kennedy's statement, Edgartown Police Chief Dominick James Arena failed to question Kennedy further and even inexplicably arranged a flight for the senator to return to his nearby hometown of Hyannis Port, Mass.

Some other inconsistencies with Kennedy's story, according to Damone, include the fact that there was a house located in the immediate vicinity of the crash site, not to mention three others along the road back to the cottage. Also, a local Deputy Sheriff, Christopher "Huck" Look, identified Kennedy's vehicle as the one he observed near the bridge on the night of the crash with "a man driving, a woman in the passenger seat, and either another person or some clothing in the back seat." Yep, the infamous "second passenger" theory, but more on that in a moment.

The televised mea culpa

After conferring with a slew of advisors for nearly a week, Ted Kennedy pleaded guilty to the single misdemeanor charge leveled at him by the Edgartown Police: leaving the scene of an accident. According to The Washington Post, Kennedy accepted a sentence of "two months in the workhouse, suspended, and a one-year suspension of his driver's license," then went on TV ten hours later to deliver his infamous public apology.

The big takeaway from the 12-minute speech was the following line: "I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately." Citing a "a jumble of emotions: grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion, and shock," Kennedy offered essentially the final explanation on his inexplicable actions during and after the incident at Chappaquiddick.

The televised address shed little light on the events of that night, other than to finally include Gargan and Markham's attempted rescue efforts. Somewhat surprisingly, Kennedy ended his remarks with a plea to the voters of Massachusetts, asking for advice on whether or not he should resign from the Senate, which, of course, he did not.

It would take another six months, and some serious legal wrangling before Kennedy would be forced to talk about Chappaquiddick under oath.

The state-ordered inquest

On Jan. 5, 1970, Sen. Ted Kennedy took the stand to testify in an inquest ordered by Massachusetts District Attorney Edmund Dinis, many portions of which we've already quoted here. According to The Washington Post, this only happened after strenuous objection from Kennedy's legal team and with an "almost diffident" Dinis at the helm, which reportedly resulted in a lackluster interrogation of Kennedy where he faced no cross-examination.

But regardless of the inquest's apparently kneecapped condition, the presiding judge, James A. Boyle, still found even more inconsistencies with Kennedy's account of the incident at Chappaquiddick. Those findings included Boyle's opinion that Kennedy's negligent driving contributed to Kopechne's death, as well as the the conclusion that he and Kopechne never intended to go to the ferry, and that they intentionally headed in the opposite direction of the ferry, destined for a secluded beach. This, of course, essentially indicated that Boyle believed Kennedy perjured himself during the inquest.

Despite Boyle's findings, no additional charges were ever filed. The results of the inquest findings were sealed "until all possibilities of further legal action against the senator had passed," according to the Christian Science Monitor. In response to Boyle's findings, Kennedy said they were "not justified and I reject them."

Upon release of the inquest in April 1970 — after a grand jury that was also convened to investigate the incident was already dismissed on legal technicalities — the rumor mill shifted into an even higher gear.

The 'second passenger' theory

We now circle back to the aforementioned "second passenger" theory, the most popular conspiracy surrounding the incident at Chappaquiddick, which suggests that Kennedy actually left the party with a different young woman, Rosemary Keough, and didn't even know Mary Jo Kopechne was in the car at all. This theory is the basis of yet another Chappaquiddick book — Kennedy once groused about there having been "upwards of twenty" written about it — written by research physicist Donald F. Nelson, called Chappaquiddick Tragedy: Kennedy's Second Passenger Revealed.

Speaking with the Cape Cod Times about his work, Nelson said that he collaborated closely with John Farrar, the "the fire department water-rescue expert" who retrieved Kopechne's body. Farrar endorsed Nelson's work so heartily, he even "wrote a blurb for the back cover." Nelson's assertion is that since Kopechne was found in the backseat and had none of the facial trauma that would have been consistent with the shattered glass from the front passenger window, combined with the fact that Keough's purse was also retrieved from the car, there must have been another passenger: Rosemary Keough.

"My book is not a work of imagination, conspiracy theories or political animus. All my conclusions are based on facts published in that era," Nelson told the Cape Cod Times. "Kennedy's Chappaquiddick accident was a historic incident in American presidential politics and thus deserves resolution. I believe I have done that."

The alleged cover-up

Yet another version of the "second passenger" theory came to light when a "retired CIA operative" told TMZ almost an identical version of Donald F. Nelson's hypothesis, with one big difference. Kennedy was allegedly having an affair with "the wife of a very powerful politician," who was supposedly also at the Chappaquiddick cottage shindig.

Here's how this theory plays out: Kennedy and the mystery mistress wanted "some alone time," so they jumped in Kennedy's car and headed for a secluded beach. However, neither bothered to check the backseat where Mary Jo Kopechne was apparently passed out drunk. The operative said that after the crash, Kennedy and lover "both swam to shore safely" and "were not injured."

As for the non-Kopechne purse found in the car? That supposedly belonged to the politician's wife, which the cops "immediately knew," and which sparked the elaborate cover-up that led to Kennedy's dubious hole-punched narrative of the incident.

Granted, this is pure speculation from an anonymous source, and even the most thorough debunking of Kennedy's testimony, like this one from The Washington Post, identifies the purse as belonging to Rosemary Keough, who requested it from the Edgartown Police after the accident. Keough was most certainly not a politician's wife, but rather another of the aforementioned "boiler room girls."

As for how her purse ended up in Kennedy's car that ill-fated evening? We'll never know, because amazingly, Edgartown Police Chief Arena never asked her.

Ted Kennedy's presidential aspirations die

Though his senate seat survived for an astonishing four more decades, Ted Kennedy never made it to a presidential candidacy. It's impossible to think the shadow of Chappaquiddick didn't have a lot — or everything — to do with that, which is a sentiment shared by many in the party who in the aftermath of the incident lamented, "Kennedy's finished," according to Newsweek.

But Kennedy did take a stab at the White House in 1980 during a contentious primary in which he tried to defeat the embattled and widely unpopular incumbent president at the time, Jimmy Carter. According to ABC News, Kennedy had a fighting chance until something entirely unrelated to Chappaquiddick derailed his opportunity.

During an interview with journalist Roger Mudd, Kennedy was asked why he wanted to be president. His answer (above) was a perplexing and vague diatribe that another journalist, who was present for the interview, seemed to think was indicative of how the so-called Lion of the Senate's heart just wasn't in it anymore.

Kennedy did manage to muster up some passion during his concession speech, known as "The Dream Shall Never Die" speech, at the Democratic National Convention, but it seemed that's exactly what had happened, at least in terms of his presidential aspirations.

Kennedy's last words on Chappaquiddick

Sen. Ted Kennedy passed away Aug. 25, 2009, making the remarks about Chappaquiddick in his posthumous memoir, True Compass, his final sentiments on the incident. Kennedy wrote that the night was "a horrible tragedy that haunts me every day of my life." He once again accepted responsibility for Mary Jo Kopechne's death and claimed that he made it a point to make nothing but apologies when it came to his public statements on the matter.

The reason for that, and for never addressing the "totally false, bizarre, and evil theories that do not deserve to be repeated" was because of the personal principle he held to "never respond to false gossip and innuendo," even when it came to matters outside of Chappaquiddick. Kennedy also wrote that a big part of his reticence toward "public discussion of that terrible night would only have caused [Joe and Gwen Kopechne, Mary Jo's parents] more pain."

That's a very interesting perspective for Kennedy to have about Kopechne's parents, because...

Mary Jo Kopechne's family still wants closure

According to E! News, on the night of Ted Kennedy's TV appearance, Joe and Gwen Kopechne gave two very different reactions to his remarks. Joe described them as "not enough," while Gwen said, "I am satisfied with the Senator's statement — and do hope he decides to stay on as Senator."

Somewhere along the way, Gwen changed her tune dramatically, telling Ladies' Home Journal (via UPI), "I think there was a big cover-up and that everybody was paid off. The hearing, the inquest — it was all a farce." She added, "The Kennedys had the upper hand, and it's been that way ever since." Both Gwen and Joe also alleged that they "didn't learn anything about [Mary Jo]'s death from [Kennedy], nor did they ever hear him say he was sorry."

The Kopechnes never pursued a lawsuit against Kennedy, but they did receive a payment of $90,904 from him, as well as a $50,000 insurance payout.

Both Joe and Gwen have passed away, but some of their surviving family members, Mary Jo's aunt, Georgetta Potoski, and her son, William Nelson, spoke with People about the film Chappaquiddick. On top of the hope that the film would "convey something about the real Mary Jo, who was reduced at the time to what William calls 'the quote-unquote Girl in the Car,'" they expressed the family's desire for further disclosure on what happened that night. "We're happy more information is coming out — that's the path to the truth."